Election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated since the 17th century. Elections may fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the executive and judiciary, and for regional and local government. This process is also used in many other private and business organisations, from clubs to voluntary associations and corporations.

The global use of elections as a tool for selecting representatives in modern representative democracies is in contrast with the practice in the democratic archetype, ancient Athens, where the elections were considered an oligarchic institution and most political offices were filled using sortition, also known as allotment, by which officeholders were chosen by lot.

Electoral reform describes the process of introducing fair electoral systems where they are not in place, or improving the fairness or effectiveness of existing systems. Psephology is the study of results and other statistics relating to elections (especially with a view to predicting future results). Election is the fact of electing, or being elected.

To elect means “to select or make a decision”, and so sometimes other forms of ballot such as referendums are referred to as elections, especially in the United States.

Candidates

A representative democracy requires a procedure to govern nomination for political office. In many cases, nomination for office is mediated through preselection processes in organized political parties.

Non-partisan systems tend to be different from partisan systems as concerns nominations. In a direct democracy, one type of non-partisan democracy, any eligible person can be nominated. Although elections were used in ancient Athens, in Rome, and in the selection of popes and Holy Roman emperors, the origins of elections in the contemporary world lie in the gradual emergence of representative government in Europe and North America beginning in the 17th century. In some systems no nominations take place at all, with voters free to choose any person at the time of voting—with some possible exceptions such as through a minimum age requirement—in the jurisdiction. In such cases, it is not required (or even possible) that the members of the electorate be familiar with all of the eligible persons, though such systems may involve indirect elections at larger geographic levels to ensure that some first-hand familiarity among potential electees can exist at these levels (i.e., among the elected delegates).

Electoral systems

Electoral systems are the detailed constitutional arrangements and voting systems that convert the vote into a political decision.

The first step is for voters to cast the ballots, which may be simple single-choice ballots, but other types, such as multiple choice or ranked ballots may also be used. Then the votes are tallied, for which various vote counting systems may be used. and the voting system then determines the result on the basis of the tally. Most systems can be categorized as either proportional, majoritarian or mixed. Among the proportional systems, the most commonly used are party-list proportional representation (list PR) systems, among majoritarian are first-past-the-post electoral system (single winner plurality voting) and different methods of majority voting (such as the widely used two-round system). Mixed systems combine elements of both proportional and majoritarian methods, with some typically producing results closer to the former (mixed-member proportional) or the other (e.g. parallel voting).

Many countries have growing electoral reform movements, which advocate systems such as approval voting, single transferable vote, instant runoff voting or a Condorcet method; these methods are also gaining popularity for lesser elections in some countries where more important elections still use more traditional counting methods.

While openness and accountability are usually considered cornerstones of a democratic system, the act of casting a vote and the content of a voter’s ballot are usually an important exception. The secret ballot is a relatively modern development, but it is now considered crucial in most free and fair elections, as it limits the effectiveness of intimidation.

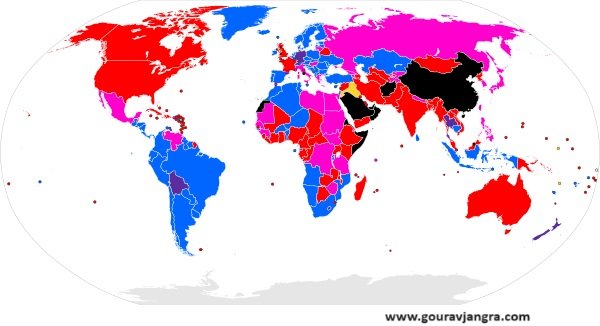

Map showing the main types electoral systems used to elect candidates to the lower or sole (unicameral) house of national legislatures, as of January 2022:

- Majoritarian representation (winner-take-all)

- Proportional representation

- Mixed-member majoritarian representation

- Mixed-member proportional representation

- Semi-proportional representation (non-mixed)

- No election (e.g. Monarchy)

Part of the Politics series

Politics

Outline . Index . Category

Top Questions:-

What is the process of election of the Indian Parliament in brief?

Elections to the Lok Sabha (and also to Vidhan Sabhas) are carried out using a first-past-the-post electoral system. The country is split up into separate geographical areas/known as constituencies, and the electors can cast one vote each for a candidate, the winner being the candidate who gets the most votes.

What is ECI?

The Election Commission of India is an autonomous constitutional authority responsible for administering Union and State election processes in India. The body administers elections to the Lok Sabha, Rajya Sabha, State Legislative Assemblies in India, and the offices of the President and Vice President in the country.

What is electoral politics class 9?

The mechanism by which people can choose their representatives at regular intervals and change them whenever they want to is called an election. In an election the voters make many choices: • They can choose who will make laws for them.

What does the Election Commission hold the election for?

The Election Commission of India is a body constitutionally empowered to conduct free and fair elections to the national, the State Legislative Assemblies, State Legislative Councils and the offices of the President and Vice-President.

Who is known as the father of Lok Sabha?

Shri Ganesh Vasudev Mavalankar

If anyone asks whose Speakership made its greatest impact on our parliamentary institutions, the answer would be, Shri Ganesh Vasudev Mavalankar, fondly remembered as Dadasaheb Mavalankar on whom the title ‘Father of the Lok Sabha’ was conferred by none other than Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru

What is the structure of the Parliament?

The parliament house of India comprises the Lok Sabha, the President, and the Rajya Sabha. The Rajya Sabha (Council of States) addresses the upper chamber and the gathering of states. On the other hand, the Lok Sabha (House of the People) is concerned with the position of persons and the lower house.

Why do we need a parliament?

The Parliament, which is made up of all representatives together, controls and guides the government. In this sense people, through their chosen representatives, form the government and also control it.

What do you mean by constituency?

A constituency is a geographical area. It is represented by a member of the state or national legislature. The people of each constituency choose one member through an election. Suggest Corrections.

What is meant by boot capturing?

Booth capturing, or booth looting, is electoral fraud in which party loyalists or hired criminals “capture” a polling booth and vote in place of legitimate voters to ensure that a particular candidate wins.

What is a reserved constituency?

Reserved constituencies are constituencies in which seats are reserved for Scheduled Castes and Tribes based on the size of their population.

What do you mean by electoral democracy?

Multiparty democracy – an electoral democracy where the people have free and fair elections and can choose between multiple political parties, unlike dictatorships that have usually one party that dominates the other parties or it is the only legally allowed party to rule.

Do you mean by electoral politics?

The country is divided into different areas for purposes of elections. These areas are called electoral constitutencies. The voters who live in an area elect one representative. So if a political party is motivated only by desire to be in power, even then it will be forced to serve the people.

What does epic stand for?

EPIC stands for Electors Photo Identity Card commonly known as Voter ID. The Indian voter ID card is an identity document issued by the Election Commission of India which primarily serves as an identity proof for Indian citizens while casting votes in the country’s state and national elections.

What is the party symbol?

| NATIONAL PARTY | ||

|---|---|---|

| S.No | Name Of Party | Symbol |

| 1 | Aam Aadmi Party | Broom |

| 2 | Bahujan Samaj Party | Elephant |

| 3 | Bharatiya Janata Party | Lotus |

| 4 | Communist Party Of India(Marxist) | Hammer, Sickle And Star |

| 5 | Indian National Congress | Hand |

| 6 | National People’s Party | Book |

| STATE PARTY | ||

| S.No | Name Of Party | Symbol |

| 1 | Indian National Lok Dal | Spectacles |

| 2 | Jannayak Janta Party | Key |

History

Elections were used as early in history as ancient Greece and ancient Rome, and throughout the Medieval period to select rulers such as the Holy Roman Emperor (see imperial election) and the pope.

The Pala King Gopala (ruled c. 750s – 770s CE) in early medieval Bengal was elected by a group of feudal chieftains. Such elections were quite common in contemporary societies of the region. In the Chola Empire, around 920 CE, in Uthiramerur (in present-day Tamil Nadu), palm leaves were used for selecting the village committee members. The leaves, with candidate names written on them, were put inside a mud pot. To select the committee members, a young boy was asked to take out as many leaves as the number of positions available. This was known as the Kudavolai system.

The first recorded popular elections of officials to public office, by majority vote, where all citizens were eligible both to vote and to hold public office, date back to the Ephors of Sparta in 754 BC, under the mixed government of the Spartan Constitution. Athenian democratic elections, where all citizens could hold public office, were not introduced for another 247 years, until the reforms of Cleisthenes. Under the earlier Solonian Constitution (c. 574 BC), all Athenian citizens were eligible to vote in the popular assemblies, on matters of law and policy, and as jurors, but only the three highest classes of citizens could vote in elections. Nor were the lowest of the four classes of Athenian citizens (as defined by the extent of their wealth and property, rather than by birth) eligible to hold public office, through the reforms of Solon. The Spartan election of the Ephors, therefore, also predates the reforms of Solon in Athens by approximately 180 years.

Questions of suffrage, especially suffrage for minority groups, have dominated the history of elections. Males, the dominant cultural group in North America and Europe, often dominated the electorate and continue to do so in many countries. Early elections in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States were dominated by landed or ruling class males. However, by 1920 all Western European and North American democracies had universal adult male suffrage (except Switzerland) and many countries began to consider women’s suffrage. Despite legally mandated universal suffrage for adult males, political barriers were sometimes erected to prevent fair access to elections.

Campaigns

When elections are called, politicians and their supporters attempt to influence policy by competing directly for the votes of constituents in what are called campaigns. Supporters for a campaign can be either formally organized or loosely affiliated, and frequently utilize campaign advertising. It is common for political scientists to attempt to predict elections via political forecasting methods.

The most expensive election campaign included US$7 billion spent on the 2012 United States presidential election and is followed by the US$5 billion spent on the 2014 Indian general election.

Election timing

The nature of democracy is that elected officials are accountable to the people, and they must return to the voters at prescribed intervals to seek their mandate to continue in office. For that reason, most democratic constitutions provide that elections are held at fixed regular intervals. In the United States, elections for public offices are typically held between every two and six years in most states and at the federal level, with exceptions for elected judicial positions that may have longer terms of office. There is a variety of schedules, for example, presidents: the President of Ireland is elected every seven years, the President of Russia and the President of Finland every six years, the President of France every five years, President of the United States every four years.

Pre-decided or fixed election dates have the advantage of fairness and predictability. However, they tend to greatly lengthen campaigns, and make dissolving the legislature (parliamentary system) more problematic if the date should happen to fall at a time when dissolution is inconvenient (e.g. when war breaks out). Other states (e.g., the United Kingdom) only set maximum time in office, and the executive decides exactly when within that limit it will actually go to the polls. In practice, this means the government remains in power for close to its full term, and chooses an election date it calculates to be in its best interests (unless something special happens, such as a motion of no-confidence). This calculation depends on a number of variables, such as its performance in opinion polls and the size of its majority.

Rolling elections are elections in which all representatives in a body are elected, but these elections are spread over a period of time rather than all at once. Examples are the presidential primaries in the United States, Elections to the European Parliament (where, due to differing election laws in each member state, elections are held on different days of the same week) and, due to logistics, general elections in Lebanon and India. The voting procedure in the Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic are also a classical example.

In rolling elections, voters have information about previous voters’ choices. While in the first elections, there may be plenty of hopeful candidates, in the last rounds consensus on one winner is generally achieved. In today’s context of rapid communication, candidates can put disproportionate resources into competing strongly in the first few stages, because those stages affect the reaction of latter stages.

Non-democratic elections

In many of the countries with weak rule of law, the most common reason why elections do not meet international standards of being “free and fair” is interference from the incumbent government. Dictators may use the powers of the executive (police, martial law, censorship, physical implementation of the election mechanism, etc.) to remain in power despite popular opinion in favour of removal. Members of a particular faction in a legislature may use the power of the majority or supermajority (passing criminal laws, and defining the electoral mechanisms including eligibility and district boundaries) to prevent the balance of power in the body from shifting to a rival faction due to an election.

Non-governmental entities can also interfere with elections, through physical force, verbal intimidation, or fraud, which can result in improper casting or counting of votes. Monitoring for and minimizing electoral fraud is also an ongoing task in countries with strong traditions of free and fair elections. Problems that prevent an election from being “free and fair” take various forms.

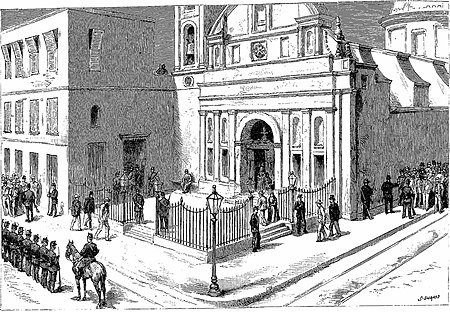

Buenos Aires 1892: "The rival voters were kept back by an armed force of police out of sight to others. Only batches of two or three were allowed to enter the polling office at a time. Armed sentries guarded the gates and the doors." Godefroy Durand, The Graphic, 21 May 1892.

Lack of open political debate or an informed electorate

The electorate may be poorly informed about issues or candidates due to lack of freedom of the press, lack of objectivity in the press due to state or corporate control, and/or lack of access to news and political media. Freedom of speech may be curtailed by the state, favouring certain viewpoints or state propaganda.

Unfair rules

Gerrymandering, exclusion of opposition candidates from eligibility for office, needlessly high restrictions on who may be a candidate, like ballot access rules, and manipulating thresholds for electoral success are some of the ways the structure of an election can be changed to favour a specific faction or candidate. Scheduling frequent elections can also lead to voter fatigue.

Interference with campaigns

Those in power may arrest or assassinate candidates, suppress or even criminalize campaigning, close campaign headquarters, harass or beat campaign workers, or intimidate voters with violence. Foreign electoral intervention can also occur, with the United States interfering between 1946 and 2000 in 81 elections and Russia/USSR in 36. In 2018 the most intense interventions, utilizing false information, were by China in Taiwan and by Russia in Latvia; the next highest levels were in Bahrain, Qatar and Hungary.

Tampering with the election mechanism

This can include falsifying voter instructions, violation of the secret ballot, ballot stuffing, tampering with voting machines, destruction of legitimately cast ballots, voter suppression, voter registration fraud, failure to validate voter residency, fraudulent tabulation of results, and use of physical force or verbal intimation at polling places. Other examples include persuading candidates not to run, such as through blackmailing, bribery, intimidation or physical violence.