Rashtrapati Bhavan

Rashtrapati Bhavan is the official residence of the president of India. When it was completed, in 1931, it was known as The Viceroy’s House after the British viceroys who ruled India in the setting years of the Raj. Its construction followed the decision to move the capital of India from Calcutta to Delhi. The principal architects of the new city were Sir Herbert Baker and Sir Edwin Lutyens.

Rashtrapati Bhavan

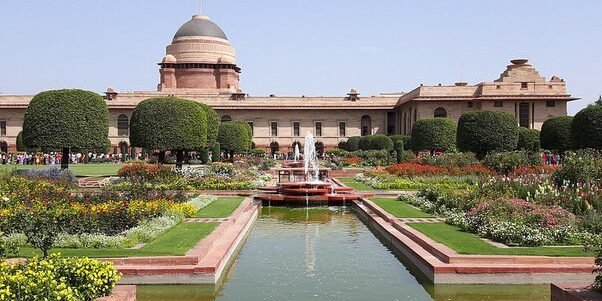

Rashtrapati Bhavan is located at the Raisina Hill end of the long, formal Raj Path, which runs from India Gate. Lutyens wanted the processional approach to be gradually inclined, focusing on the house’s dome, but Baker was allowed to retain the level space between his two Secretariat Buildings, which frame the Raj Path. Lutyens was upset by this decision; he called it his “Bakerloo.” Today, though, the approach to the house reveals itself dramatically as you crest the hill, so perhaps Baker’s decision was the right one. This palatial house consists of a central block capped by a copper dome 177 feet (54 m) high, and four wings. Thirty-two broad steps lead to the portico and the main entrance of the Durbar Hall. The hall is a circular marble court, 75 feet (23 m) across. Off this are wings containing private apartments, 54 bedrooms, accommodation for more than 20 guests, offices, kitchens, a post office, and courtyards and loggias. The house is 600 feet (183 m) long. It covers 4.5 acres (1.8 ha) and used 9.8 million cubic feet (279,000 cu m) of stone. The colours of the stone are subtle and carefully considered: the lower parts are in deep red sandstone, the upper parts cream. A thin red stone line is inserted at the parapets, contrasting with the blue sky most effectively. The Moghul Gardens—designed by Lutyens, working with William Robertson Mustoe—are patterned geometrically with red and buff sandstone. (Aidan Turner-Bishop)

The Rāṣṭrapati Bhavan is the official residence of the President of India at the western end of Rajpath, Raisina Hill, New Delhi, India. It was formerly known as Viceroy’s House and constructed during the zenith of British Empire. Rashtrapati Bhavan may refer to only the 340-room main building that has the president’s official residence, including reception halls, guest rooms and offices, also called the mansion; it may also refer to the entire 130-hectare (320-acre) Presidential Estate that additionally includes the presidential gardens, large open spaces, residences of bodyguards and staff, stables, other offices and utilities within its perimeter walls. In terms of area, it is the second largest residence of any head of state in the world after Quirinal Palace in Italy. The other presidential homes are the Rashtrapati Nilayam in Hyderabad, Telangana and The Retreat Building in Shimla, Himachal Pradesh.

History

The Governor-General of India resided at Government House in Calcutta until the shift of the imperial capital to Delhi. Lord Wellesley, who is reputed to have said that ‘India should be governed from a palace, not from a country house’, ordered the construction of this grand mansion between 1799 and 1803 and in 1912, the Governor of Bengal took up residence there. The decision to build a residence in New Delhi for the British Viceroy was taken after it was decided during the Delhi Durbar in December 1911 that the capital of India would be relocated from Calcutta to Delhi. When the plan for a new city, New Delhi, adjacent to the end south of Old Delhi, was developed after the Delhi Durbar, the new palace for the Viceroy of India was given an enormous size and prominent position. About 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of land was acquired to begin the construction of Viceroy’s House, as it was originally called, and adjacent Secretariat Building between 1911 and 1916 by relocating Raisina and Malcha villages that existed there and their 300 families under the Land Acquisition Act, 1894.

The British architect Edwin Landseer Lutyens, a major member of the city-planning process, was given the primary architectural responsibility. The completed Governor-General’s palace turned out very similar to the original sketches which Lutyens sent Herbert Baker, from Shimla, on 14 June 1912. Lutyens’ design is grandly classical overall, with colours and details inspired by Indo-Saracenic architecture. Lutyens and Baker, who had been assigned to work on Viceroy’s House and the Secretariats, began on friendly terms. Baker had been assigned to work on the two secretariat buildings which were in front of the Viceroy’s House. The original plan was to have Viceroy’s House on the top of Raisina Hill, with the secretariats lower down. It was later decided to build it 400 yards back and put both buildings on top of the plateau.

Lutyens campaigned for its fixing but was not able to get it to be changed. Lutyens wanted to make a long inclined grade to Viceroy’s House with retaining walls on either side. While this would give a view of the house from further back, it would also cut through the square between the secretariat buildings. The committee with Lutyens and Baker established in January 1914 said the grade was to be no steeper than 1 in 25, though it eventually was changed to 1 in 22, a steeper gradient which made it more difficult to see the Viceroy’s palace. While Lutyens knew about the gradient and the possibility that the Viceroy’s palace would be obscured by the road, it is thought that Lutyens did not fully realise how little the front of the house would be visible.

Rashtrapati Bhavan

(Rāṣṭrapati Bhavan)

Top: the Presidential Palace’s forecourt with T shaped ceremonial reception ground facing the Jaipur Column

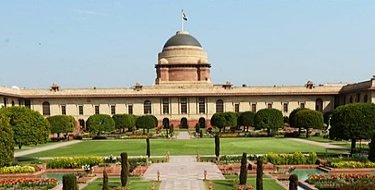

Bottom: the Presidential Palace’s backyard with square shaped central lawn facing the Amrit Udyan Gardens

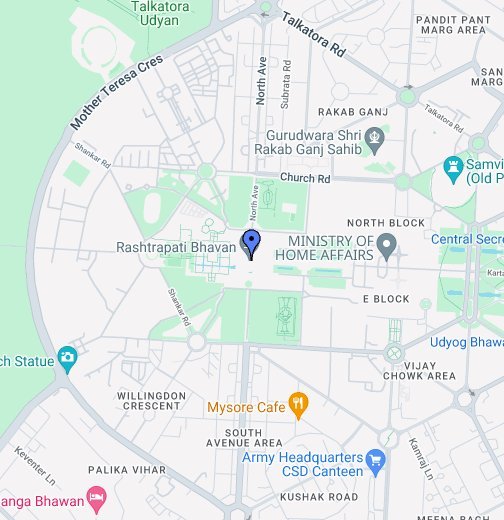

location map of Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi, India

| Former names | Viceroy’s House (until 1947) Government House (1947–1950) |

|---|---|

| Alternative names | Presidential House |

General information

| Architectural style | Delhi Order |

|---|---|

| Location | Rajpath, Raisina Hill, New Delhi |

| Address | Rastrapati Bhavan, New Delhi, India – 110 004 |

| Town or city | New Delhi |

| Country | India |

| Current tenants |

|

| Construction started | 1912 |

| Completed | 1929 |

| Opened | 1931 |

| Owner | Government of India |

| Height | 55 meters |

Technical details

| Size | 130 hectare (321 acre) |

|---|---|

| Floor count | Four |

| Floor area | 200,000 sq ft (19,000 m2) |

Design and construction

| Architect(s) | Sir Edwin Lutyens |

|---|

Other information

| Number of rooms | 340 |

|---|

In 1916 the Imperial Delhi committee dismissed Lutyens’s proposal to alter the gradient. Lutyens thought Baker was more concerned with making money and pleasing the government, rather than making a good architectural design. The land was owned by Basakha Singh and mostly Sir Sobha Singh.

Lutyens travelled between India and England almost every year for twenty years and worked on the construction of the Viceroy’s House in both countries. Lutyens reduced the building from 13,000,000 cubic feet (370,000 m3) to 8,500,000 cubic feet (240,000 m3) because of budget restrictions.

The gardens were initially designed and laid out in Mughal style by William Robert Mustoe who was influenced by Lady Hardinge who in turn had sought inspiration in the book by Constance Villiers-Stuart in her Gardens of the Great Mughals (1913). The designs underwent changes and alterations under subsequent viceroys and after Indian Independence. After independence, it was renamed as Government House.

When Chakravarti Rajagopalachari assumed office as the first India-born Governor General of India and became the occupant of this palace, he preferred to stay in a few rooms in the former Guest Wing, which is now the family wing of the President; he converted the then Viceroy’s apartments into the Guest Wing, where visiting heads of state stay while in India.

On 26 January 1950, when Rajendra Prasad became the first President of India and occupied this building, it was renamed Rashtrapati Bhavan – the President’s House.

Sloping approach from the east

Architecture

Design

Consisting of four floors and 340 rooms, with a floor area of 200,000 square feet (19,000 m2), it was built using 700 million bricks and 3,000,000 cu ft (85,000 m3) of stone with little steel.

The design of the building fell into the period of the Edwardian Baroque, a time at which emphasis was placed on the use of heavy classical motifs to emphasise power. The design process of the mansion was long, complicated and politically charged. Lutyens’ early designs

were all starkly classical and entirely European in style, although he wished to do it in classical Indian style- India never had a uniform architecture for public use. In the post-Mutiny era, however, it was decided that sensitivity must be shown to the local surroundings to better integrate the building within its political context, and after much political debate, Lutyens conceded to incorporating local Indo-Saracenic motifs, albeit in a rather superficial decoration form on the skin of the building.

Various Indian elements were added to the building. These included

several circular stone basins on top of the building, as water features are an important part of Indian architecture. There was also a traditional Indian chujja or chhajja, which occupied the place of a frieze in classical architecture; it was a sharp, thin, protruding element which extended 8 feet (2.4 m) from the building, and created deep shadows. It blocks harsh sunlight from the windows and also shields the windows from heavy rain during the monsoon season. On the roofline were several chuttris, which helped to break up the flatness of the roofline not covered by the dome. Lutyens appropriated some Indian design elements but used them sparingly and effectively throughout the building.

The column has a “distinctly peculiar crown on top, a glass star springing out of bronze lotus blossom”.

There were pierced screens in red sandstone, called jalis or jaalis, inspired by Rajasthani designs. The front of the palace, on the east side, has twelve unevenly spaced massive columns with the Delhi Order capitals, a “nonce order” Lutyens invented for this building, with Ashokan details. The capitals have a fusion of acanthus leaves with the four pendant Indian bells. The bells are similar in style to Indian Hindu and Buddhist temples, the idea is inspired by a Jain temple at Moodabidri in Karnataka.

One bell is on each corner at the top of the column. As there is an ancient Indian belief that bells signalled the end of a dynasty, it was said that as the bells were silent British rule in India would not end.

Whereas previous British examples of so-called Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture had mostly grafted elements from Mughal architecture onto essentially Western carcasses, Lutyens drew also from the much earlier Buddhist Mauryan art. This can be seen in the Delhi Order, and in the main dome, where the drum below has decoration recalling the railings around early Buddhist stupas such as Sanchi. There is also the presence of Mughal and European colonial architectural elements. Overall the structure is distinctly different from other contemporary British Colonial symbols, although other New Delhi buildings, such as the Secretariat Building, New Delhi, mainly by Herbert Baker, have similarities e.g. both are built with cream and red Dholpur sandstone.

Lutyens added several small personal elements to the house, such as an area in the garden walls and two ventilator windows on the stateroom to look like the glasses which he wore. The Viceregal Lodge was completed largely by 1929, and (along with the rest of New Delhi) inaugurated officially in 1931. Between 1932 and 1933 important decorations were added, especially in the ballroom, and executed by the Italian painter Tommaso Colonnello.